In this three-part series, TransPar Group takes an analytical look at the driver shortage plaguing the school transportation industry. By analyzing system efficiencies and budgetary considerations, TransPar offers an approach to how school administrators and transportation professionals alike can look beyond the surface issues and understand how a combined approach of technological expertise and creative retention strategies can go a long way towards solving the driver staffing crisis.

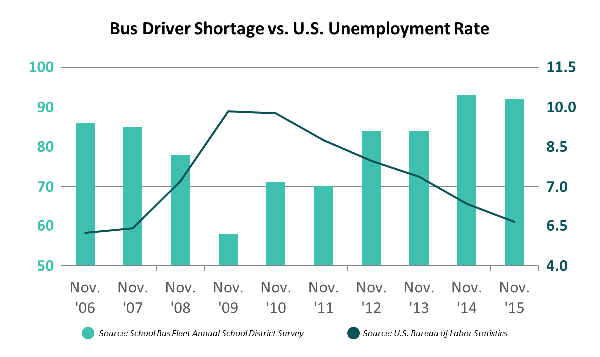

The economy in the United States is growing, with 100,000 more jobs available than unemployed Americans to fill them. Additionally, wage growth is now starting to find its way into the economy at a rate not seen during the previous 9 years of economic growth. With a historically low unemployment rate – just 3.9% nationally as of July 2018 – finding qualified workers has become increasingly difficult for employers.

In some metro areas, the transportation industry is experiencing unemployment rates of less than three percent, with the starting wage for many CDL passenger transportation drivers at more than $17 an hour. This is tremendous news for a professional driver force that has long been seeking and deserving of a more competitive wage. However, when you stop to consider the source of the driver shortage plaguing the school transportation industry, it must be recognized that this is more than just an issue of wages. Other macro factors in the marketplace are increasing the demand for professional drivers, while the tightening of budgets, more school choice options, and the “Uberfication” of transportation are all negatively impacting the overall driver supply.

When assessing the causes of the bus driver shortage, one must take into account the continuing strain on state and local budgets. When education funding is cut, school boards and superintendents work hard to protect their teachers and students, sparing classrooms and educational activities to the greatest extent possible. Support services, including administrative, janitorial, food services and transportation, are much more likely to take the brunt of state or local funding decreases.

Students and their families also have more options than ever before when it comes to K-12 education. From public and private school, to parochial, Montessori, charter, magnet and everything else in between, more choices in schools and a reduction in the use of traditional attendance zoning results in more complex – and thereby, less efficient – school transportation. More options result in the need for more buses, which result in the need for more drivers, which result in increasing costs. Some cities, like Denver, Colorado, have been very public in their support of students and parents exercising their options to choose the school best suited for them; however, transportation policy, funding, and resources are difficult to align with the program given these macro-level challenges.

School programs, extracurricular activities, and even movements like Start School Later increase the complexity of a school’s transportation system, while the rise of rideshare services such as Uber and Lyft, provide potential school bus drivers with more options for gainful income.

So, we have found ourselves in a situation where the market is deficient of the resources schools and school districts need to support the demands of current school transportation systems.

Check out Part II of our series where we address the broader issue of defining the expectations for school transportation, and how we can support those expectations with highly integrated technologies. Only then will we be able to design transportation systems that have any chance of meeting the expectations of parents, students, and administrators.